UK Struggles With Junior Doctor Shortage: Challenges in Junior Doctor Training Allocation

The NHS is facing a pressing need for more doctors, as evidenced by the record number of applications from medical students for junior doctor training this year. However, a closer look reveals that many of these aspiring doctors are encountering difficulties in securing employment. What are the underlying issues contributing to this problem?

One factor exacerbating the situation is the surge in the number of medical students entering junior doctor training this summer. Over 9,700 students were accepted into the UK Foundation Programme, a significant increase from the previous year’s figure of 8,655. While this influx is a positive development in addressing the shortage of doctors, it has posed challenges for NHS trusts in providing an adequate number of training posts for the new graduates.

A notable portion of these medical students may have come from abroad, complicating the allocation process due to immigration regulations that prevent the NHS from prioritizing UK-trained students. Consequently, the distribution of training posts becomes more complex, further exacerbating the shortage of doctors within the NHS.

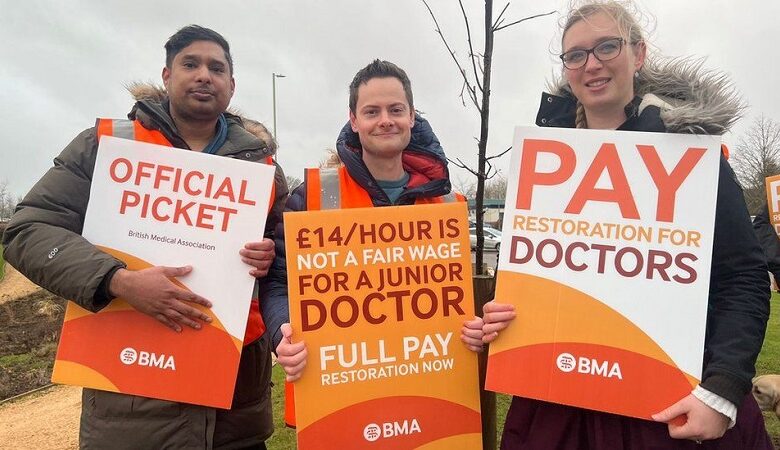

The British Medical Association (BMA) has raised concerns about the situation, highlighting the uncertainty faced by many medical students regarding their placements. Students have expressed frustration at the lack of clarity, with some reporting that they may only receive information about their placements three weeks before their scheduled start date in August, contrary to the standard practice of confirming work schedules at least eight weeks in advance.

Allocation of placements has also undergone changes, adding to the challenges faced by medical students. In the past, students were assigned to regions based on merit, considering their academic performance and test results. However, this year, allocations have been randomized to address concerns about fairness, particularly for students from disadvantaged backgrounds and ethnic minorities. While this change aimed to alleviate stress and promote equity, it has resulted in more students not receiving their preferred placements.

The allocation process is further complicated by the large geographical areas covered by some foundation school areas. While Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland each have their own foundation school, England’s Yorkshire and Humber region encompasses a vast area, posing logistical challenges for both students and NHS trusts.

Despite these challenges, efforts are underway to address the shortage of doctors and streamline the allocation process. Dr. Celia Bielawski, from the North London Foundation School, emphasized the collaborative efforts of deaneries and NHS trusts in creating additional junior doctor posts. While acknowledging the need to accommodate international medical graduates, she expressed confidence that all students would eventually be placed in training posts.

Prof. Sheona Macleod, director of education and training at NHS England, echoed this optimism, assuring that every effort is being made to find placements for all medical students. However, she acknowledged the persistent anxiety among students due to uncertainties surrounding placements.

In conclusion, the challenges in junior doctor training allocation highlight the complexities of addressing the shortage of doctors within the NHS. While efforts are underway to overcome these obstacles, it is crucial to ensure a fair and efficient allocation process that prioritizes the needs of both medical students and healthcare providers.