How the Surrealist Movement Shaped the Course of Art History

News Mania Desk / Piyal Chatterjee / 8th February 2025

At the 1936 International Surrealist Exposition in London, guest speaker Salvador Dalí spoke to the audience while dressed completely in a vintage scuba suit. He was holding two dogs on leashes in one hand and a pool cue in the other. During the lecture, hindered by the scuba mask, the Spanish artist started to choke and waved his arms for assistance. The spectators, undisturbed, believed his movements were merely a part of the act. According to art legend, the Surrealist poet David Gascoyne ultimately saved Dalí, who, once he recovered, stated, “I simply aimed to demonstrate that I was diving profoundly into the human psyche.” Dalí subsequently concluded his address. As expected, the slides he presented were all upside down.

This story highlights the most absurd, almost comedic aspects of the Surrealist movement, epitomized by Dalí—who was regarded as somewhat of a laughingstock by the early 20th-century art community. However, the art movement was indeed much more varied than is commonly recognized, encompassing multiple disciplines, styles, and regions from 1924 until it concluded in 1966.

Established by the poet André Breton in Paris in 1924, Surrealism was a movement in art and literature. It suggested that the Enlightenment—an impactful intellectual movement of the 17th and 18th centuries that advocated for reason and individualism—had stifled the exceptional attributes of the irrational, unconscious mind. The aim of surrealism was to free thought, language, and human experience from the restrictive limits of rationalism.

Breton had pursued studies in medicine and psychiatry and was knowledgeable about the psychoanalytical works of Sigmund Freud. He was especially fascinated by the notion that the unconscious mind, which generated dreams, was the origin of artistic creativity. A committed Marxist, Breton aimed for Surrealism to act as a revolutionary force that would liberate the minds of the masses from society’s rational constraints. However, what methods could they use to attain this freedom of thought?

Automatism, a technique similar to free association or stream of consciousness, provided the Surrealists a way to create artwork from the unconscious mind. Surrealist artist André Masson’s mixed-media artwork Battle of Fishes (1926) serves as an early illustration of automatic painting. To start, Masson used gesso—a sticky material often employed to prepare surfaces for painting—and allowed it to drop freely onto his canvas. He subsequently scattered sand over it, allowing the grains to adhere to the glue haphazardly, and sketched and painted around the shapes that emerged. Artists using automatic techniques welcomed the factor of chance, frequently yielding unexpected outcomes. Masson’s final creation depicts two ancient fish, their jaws stained with blood, battling in the primordial sludge: an unintentional showcase of nature’s inherent brutality.

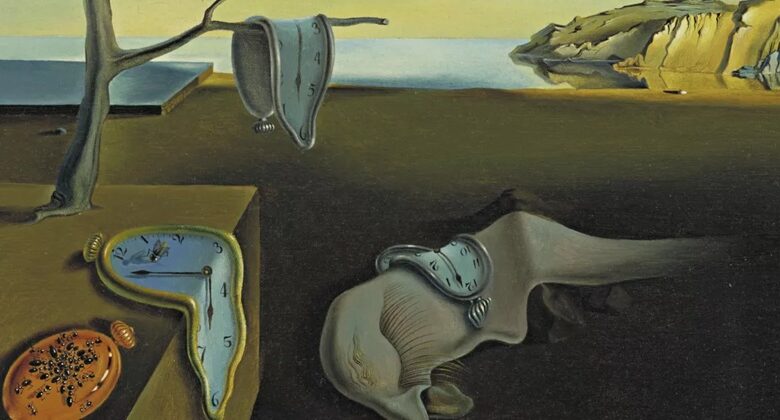

Nonetheless, not all Surrealists opted to produce works that were so abstract. Numerous Surrealists acknowledged that depicting a thing’s true appearance in the physical realm could more powerfully evoke associations for the viewer, uncovering a deeper, unconscious reality. Artists such as Dalí and the Belgian painter René Magritte produced hyper-realistic, surreal images that serve as portals into an unusual realm beyond ordinary existence. Magritte’s La Clairvoyance (1936) features an artist who depicts a flying bird while gazing at an egg resting on a table, evoking a dreamlike or hallucinatory atmosphere.

Although Surrealism is primarily linked to bold and unconventional personalities like Dalí, Breton enlisted a diverse range of artists and thinkers already engaged in Paris to contribute to and showcase under his movement. Drawing from the anti-rational legacy of Dada, Surrealism included prominent Dada artists such as Tristan Tzara, Francis Picabia, Jean Arp, Max Ernst, and Marcel Duchamp among its ranks. By 1924, this collective expanded to include additional artists and literary individuals, such as authors Paul Éluard, Robert Desnos, Georges Bataille, and Antonin Artaud; painters Joan Miró and Yves Tanguy; sculptors Alberto Giacometti and Meret Oppenheim; and filmmakers René Clair, Jean Cocteau, and Luis Buñuel.

However, Breton was infamously capricious regarding whom he allowed into the movement, and he often excommunicated individuals he believed had drifted from his specific interpretation of Surrealism. For instance, Desnos and Masson were expelled from the group by Breton’s “Second Manifesto of Surrealism” in 1930 due to their refusal to back his political goals. Bataille, whose Surrealist perspective was quite different from Breton’s, went on to establish his own significant faction, the College of Sociology, which released journals and organized exhibitions during the 1930s.

Surrealism embodies a melting pot of avant-garde concepts and methods that modern artists still employ, such as incorporating chance elements into their artwork. These techniques introduced a fresh approach to painting adopted by the Abstract Expressionists. The aspect of luck has been essential to performance art, evident in the unscripted Happenings of the 1950s, and it extends to computer art that utilizes randomness. The Surrealist emphasis on dreams, psychoanalysis, and imaginative visuals has inspired several contemporary artists, including Glenn Brown, who has directly borrowed from Dalí’s artwork in his own creations. Surrealism’s ambition to escape reason prompted a reevaluation of the fundamental basis of artistic creation: the notion that art is the result of an individual artist’s inventive mind. To counter this, Breton advocated for the cadavre exquis, or “exquisite corpse,” as a method for collaboratively producing art, a practice that remains popular as a game even today. It consists of beginning a sentence, drawing, or collage, and then passing it to someone else to carry on—without allowing that person to view what has previously been written, illustrated, or arranged. The phrase originated from a straightforward game of forming collective prose that led to the sentence, “The exquisite corpse shall drink the new wine.”

Due to the method’s acceptance of randomness and its inclination to generate humorous, bizarre, or disturbing images, it quickly evolved into an effective approach for crafting the precise kind of subconscious, communal art that the Surrealists aimed for. Exquisite Corpse 27 (approximately. 2011), a project finalized by Ghada Amer, Will Cotton, and Carry Leibowitz, serves as a modern illustration of the stylistically and thematically disjointed creations that can emerge from this Surrealist approach. The historian and music critic Greil Marcus has even described Surrealism as a segment in a continuum of revolutionary efforts aimed at freeing thought, which extends from the heresies of medieval dissenters to the 1960s and further. In this context, Surrealism can be seen as the precursor to the later, Marx-influenced art movement Situationism, 1960s countercultural demonstrations, and even punk: an initiative aimed at dismantling the rational structure imposed by society on individuals.