After a week of tumult, will South Korea impeach its president?

News Mania Desk / Piyal Chatterjee / 13th December 2024

Is South Korea’s president, Yoon Suk Yeol, on the verge of being removed from office for proclaiming martial law last week?

The question, which has hounded Yoon during a series of opposition measures to end his presidency, will be raised again tomorrow, when parliament attempts to impeach him for the second time. The besieged leader pledged to “fight until the end to prevent the forces and criminal groups that have been responsible for paralysing the country’s government and disrupting the nation’s constitutional order from threatening the future of the Republic of Korea” .

Following Yoon’s perplexing late-night martial law declaration on December 3, political upheaval and massive protests by irate South Koreans have ensued over the last week. As parliament consider impeachment, investigations into Yoon’s proclamation have been accompanied by the incarceration of high-ranking officials. Today’s newsletter outlines all you need to know about one of the most politically charged weeks in recent South Korean history. First, here are the headlines.

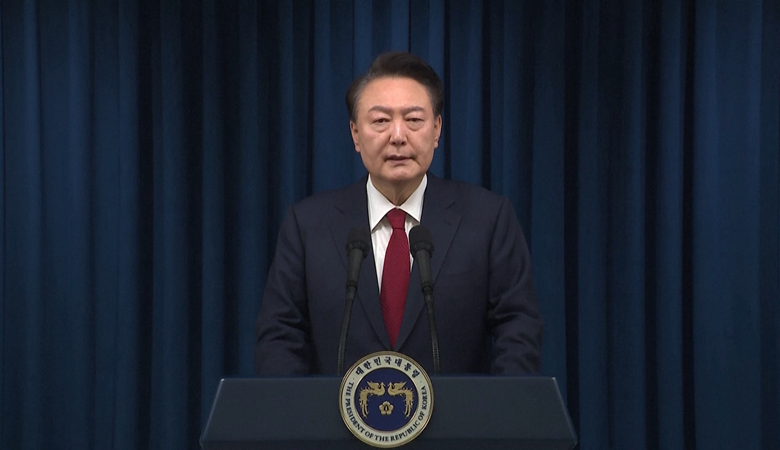

The South Korean opposition has condemned Yoon’s brief declaration of martial law as a “unconstitutional, illegal rebellion or coup,” and yesterday’s televised statement by the president as “an expression of extreme delusion” and “false propaganda.” However, with 192 seats in the 300-member National Assembly, it requires support from at least eight members of the president’s conservative governing party.

Yoon’s statement yesterday appeared to be intended to persuade parliamentarians that his martial law declaration is a legitimate act of government that cannot be investigated and does not constitute rebellion. He stated that the deployment of over 300 soldiers to the national assembly was intended to maintain order, not dissolve or paralyze it. And he branded the opposition as “a monster” and “anti-state,” attempting to use its parliamentary authority to impeach key officials, undermining the government’s budget plan for the coming year, and sympathizing with North Korea.

The speech was interpreted as a reversal by the president, who had apologised last week for proclaiming martial law and stated that he would not avoid responsibility for it. Kim Min-seok, leader of a Democratic party taskforce, called the address “a declaration of war against the people” and accused the president of aiming to stir disturbances by far-right forces supportive of him. He stated that the Democratic Party’s priority will be on passing the impeachment motion against Yoon.

Yoon has had little success getting his proposals passed by an opposition-controlled parliament since he entered office in 2022. Conservatives have argued the opposition’s attempts are political vengeance for probes into Democratic party head Lee Jae-myung, who is viewed as the favorite in the next presidential election due in 2027.

Yoon has denied misconduct in an influence-peddling controversy involving him and his wife. The claims have lowered his approval rating and fueled attacks from his opponents. The scandal revolves upon allegations that Yoon and first lady Kim Keon Hee used inappropriate influence on the governing party to select a certain candidate for a 2022 parliamentary byelection. Yoon claims he did nothing inappropriate.South Korea’s constitution empowers the president to use the military to maintain order in “wartime, war-like situations, or other comparable national emergency states”. Martial law powers can include suspending civil liberties like press freedom and assembly, as well as temporarily limiting the power of judges and government bodies.

The constitution also empowers the national assembly to lift martial law by a majority vote. Lawmakers hurried to the assembly building as soon as they learned about Yoon’s declaration last week. Some climbed the walls to circumvent a military cordon and form a quorum. The vote to lift the injunction was 190-0, including 18 members of Yoon’s own party.

The impeachment resolution on the table presently claims that Yoon declared martial law much beyond his legal authority and in a situation that did not fulfill the constitutional requirement of a critical crisis. The constitution also prohibits a president from using the military to suspend parliament.

Police, prosecutors, and other authorities are looking into whether Yoon and those engaged in the martial law declaration committed insurrection, misuse of power, or other offenses. Earlier this week, the justice ministry prohibited Yoon from leaving the nation, although it is uncertain whether they will be able to jail or arrest the president. South Korean law protects a president from prosecution while in office, with the exception of insurrection or treason charges. This means that Yoon can be questioned and jailed over his martial law order, although many analysts doubt that authorities will act strongly due to the possibility of conflicts with his presidential security service. On Wednesday, Yoon’s security force refused to allow authorities to examine the presidential office.

Meanwhile, Yoon’s former defense minister, Kim Yong-hyun, attempted suicide at a Seoul prison center on Wednesday night but was stopped by correctional guards. He was detained on charges of having a crucial role in a revolt and abuse of power, making him the first person formally arrested under the martial law declaration. Kim, who resigned after martial law was lifted, is one of Yoon’s close colleagues. He has been accused of advocating the move to Yoon and deploying troops to the National Assembly to prevent MPs from voting. According to officials, Kim’s condition is stable.The country’s police commander and the head of Seoul’s metropolitan police were both detained for sending their forces to the national parliament.

Thousands of demonstrators have marched through Seoul’s streets, calling for Yoon’s dismissal. Autoworkers and other members of the Korean Metal Workers’ Union, one of the nation’s largest umbrella labor organizations, have begun hourly strikes.

During the dictatorships that formed as South Korea rebuilt after the 1950-53 Korean War, leaders occasionally declared martial law, allowing them to post soldiers, tanks, and armored vehicles on the streets or in public areas to suppress anti-government protests. Army General Park Chung-hee led several thousand troops into Seoul early on May 16, 1961, in the country’s first coup. He led South Korea for nearly two decades, declaring martial law multiple times to quell protests and imprison dissidents until being killed by his intelligence chief in 1979.

Less than two months after Park’s death, Maj Gen Chun Doo-hwan led tanks and troops into Seoul in December 1979, sparking the country’s second coup. The following year, he led a savage military response on a pro-democracy uprising in the southern city of Gwangju, killing at least 200 people. In the summer of 1987, enormous street protests compelled Chun’s government to concede to direct presidential elections. His army comrade Roh Tae-woo, who had participated in Chun’s 1979 coup, won an election later in 1987, owing to a split vote among liberal opposition candidates.

The main opposition Democratic Party filed a new impeachment resolution against Yoon Tuesday, setting up a vote this weekend. It will require two-thirds approval in parliament to pass. The first impeachment attempt failed last week when the majority of MPs from Yoon’s ruling People Power party skipped the vote. However, the president’s address yesterday is expected to exacerbate the division inside the PPP. When party chair Han Dong-hoon, a critic of Yoon, labeled Yoon’s statement “a confession of rebellion” during a party meeting, Yoon supporters booed and demanded that Han cease speaking. Han pushed party members to vote in favor of Yoon’s impeachment.

If Yoon is eventually impeached, he will be suspended until the constitutional court decides whether he should be removed from office. Prime Minister Han Duck-soo, the government’s second-in-command, would assume presidential responsibilities. If he is ousted from office, a new presidential election must be held within 60 days.