An AI Ghibli image might do more harm than you think…

News Mania Desk / Piyal Chatterjee / 28th March 2025

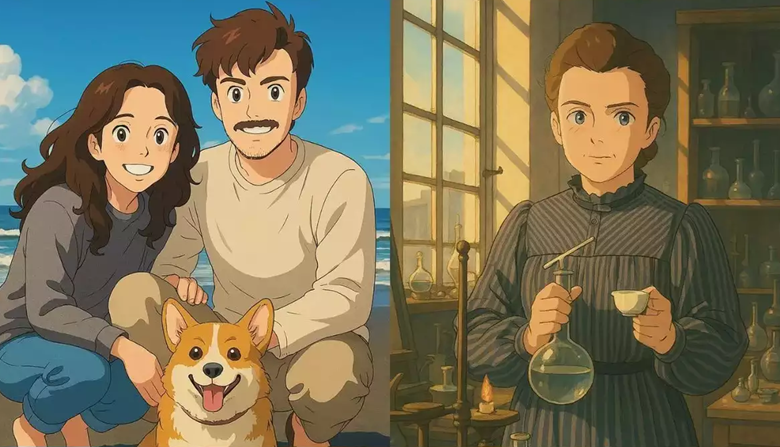

The pink skies, large eyes, and ethereal glow that suddenly appeared on my social media thrilled me for a brief moment about an upcoming Studio Ghibli movie. Another moment spent observing, and the synthetic origins of the images became as evident as my aversion to their proliferation. The viral Ghibli images created by ChatGPT this week are not generated with any harmful intent, yet they exemplify the negative aspects of AI-generated content.

If you’ve missed the recent AI blunder, it stems from OpenAI’s new enhancement to ChatGPT, an advanced image generator that surpasses the existing DALL-E model and excels at imitating artistic styles. When we refer to art styles, it’s not merely “Renaissance” or “Dutch Old Master”; it encompasses particular artists and studios. Unsurprisingly, someone discovered that you could prompt it to create images reminiscent of a Ghibli film, leading to an influx of creativity. Animals, infants, companions, stars, memes, and all other things are receiving the AI Ghibli makeover.

Certain results are stunning. A few are odd. They all somewhat remind one of Ghibli. Yet that’s precisely the case; they summon, resonate, and replicate. They’re the AI counterpart of listening to a tribute band perform a nearly flawless rendition of “Let It Be.” You may experience some of the same sensation as listening to the original, but it won’t be entirely accurate, and attempting to compel it will only worsen the situation.

Studio Ghibli’s movies are intentionally, nearly radically, slow in their style and creation. They stop in spots where many movies advance to allow you to appreciate the beauty of the flowing wind through the grass or the intricacies of a deserted street. The artwork is not only beautiful; every frame is filled with attention and skill.These movies are created manually, over many years, by individuals who infuse energy into each frame. Processed and spit out by AI misses the essence to a humorous extent. Returning to the music analogy, it’s akin to having symphony tickets but opting to perform Mozart on a kazoo and appreciating it just as much. This doesn’t imply that the AI-generated images lack accuracy. It makes you think about whether it was trained on Ghibli’s creations.

If that’s the case, it was certainly done without the consent of Ghibli founder Hayao Miyazaki. His contempt for art produced by AI is quite obvious. In a 2016 documentary, he reacted to viewing an AI animation demonstration with clear disgust and referred to it as “an affront to life itself.” That may seem exaggerated, yet it wasn’t theatrical or solely indicative of a monetary issue. The company asserts that they have limited users from requesting ChatGPT to create images that replicate the work of certain living artists. That’s an initial step. However, it does not pertain to studios or creators who have died, nor does it seem to safeguard the legacy of those like Hayao Miyazaki, who is still alive yet feels strangely vulnerable here.

Numerous people contend that art should be accessible to everyone, and this OpenAI update enhances its accessibility, enabling anyone with internet access to create whatever they desire. Besides the uncertainty surrounding whether the new feature infringes on copyright regulations, what does it indicate about those who have spent years honing their skills? What does it reveal about Eiji Yamamori, who animated the four-second moment in The Wind Rises, and the weeks he dedicated to drawing and redrawing characters that have such minimal screen presence? For a generation that swipes through reels at lightning speed, it might appear that Yamamori was ‘unproductive’ or ‘delaying’. For the Japanese, who consistently top the global charts for longevity, happiness, and health, the animator’s lengthy quest for excellence connects to their dual philosophies of ‘ikigai’ (discover your purpose and diligently refine it) and ‘kaizen’ (making incremental progress for greater outcomes). Many of us can only hope to love doing something as much as Yamamori loved animating that scene.

The conflict between AI and artists persists. Only last year, over 13,000 creators globally, including renowned artists, musicians, and writers such as Julianne Moore, Thom York, and Kazuo Ishiguro, endorsed a declaration informing AI firms that the unauthorized use of their creations to develop generative AI systems poses a “significant, unfair danger” to their careers. Recently, after receiving the best actor award for Dream Scenario (2023) at the Saturn Awards last month, Nicolas Cage stated, “I firmly believe we should not allow robots to dream on our behalf.” No one can claim their concerns are baseless. How could we possibly create a masterpiece like Boyhood (2014), where director Richard Linklater filmed lead actor Ellar Coltrane for 12 years to accurately capture their physical evolution, if AI can quickly age a person in just a few hours?

In addition to artistic, ethical, and moral issues, AI raises significant environmental worries. Research has shown that whenever you utilize AI to create an image, compose an email, or pose a question to a chatbot, it has an environmental impact. A study by the Washington Post, in partnership with the University of California, Riverside, indicates that ChatGPT consumes 519 millilitres—slightly more than one bottle—of water to generate a 100-word email. And transforming yourself or a specific scene from your favorite film into Ghibli style? Evidently, that uses up as much power as completely charging your smartphone. Immediately after the OpenAI update was launched last night, AI filmmaker PJ Ace debuted a 1 minute 52 second trailer for a Ghibli adaptation of The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001). Somewhere, a body of water has vanished completely.