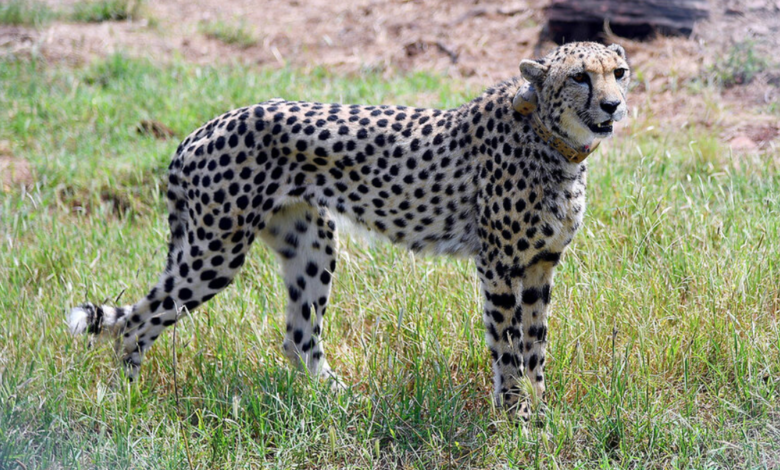

Bringing African Cheetahs To India Has Additional Issues

Four difficulties under Indian and international wildlife law now arise as a result of the introduction of African cheetahs from Namibia to Kuno National Park.

First, the Wildlife Act of 1972 includes cheetahs under Schedule I. Will an African cheetah, which is a distinct subspecies from the Asiatic cheetah, automatically be listed as a threatened species under the WLPA?

If so, has its hunting, which includes actions like capture and release, been authorized by the proper statutory body after receiving consent from the Indian government? Because the African cheetah is an exotic animal that Indian authorities cannot be expected to manage based on circumstances set by Indian law, the question is puzzling.

This is relevant to the second issue since the CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) Agreement, to which India is a signatory, governs the international movement of wild endangered animals. If African cheetahs are not considered wild animals under the WLPA, then CITES regulations would have applied to their international transfer.

Before introducing African cheetahs to India, did government officials acquire CITES authorization in both Namibia and India? We don’t know whether the Namibian government actually granted a CITES license to transport cheetahs to India. The existence of an Indian customs facility at the Gwalior airport, where authorities handled the CITES clearance, is also questionable.

Third, is Kuno National Park’s cheetah cage a zoo?

According to Indian wildlife law, a zoo is any facility that houses animals in captivity for public display. The African cheetahs in Kuno are undoubtedly captive animals. They will be kept in an enclosure that will allow for public viewing because, otherwise, how can tourism be improved? Since it is intended to release the cheetahs into an area free of walls after a month, the cheetah enclosure in Kuno is therefore officially a zoo, even if only temporarily.

And is it allowed to build such a facility inside a national park, even if it’s only temporary?

The Union Environment Ministry informed state governments in a letter dated June 8, 2022, that government zoos in forested regions might be constructed with the proper approval obtained from the Central Zoo Authority. Zoos should be avoided in protected regions (including national parks), the letter continued, and should only be situated on the edge of buffer zones in exceptional circumstances.

Therefore, given that the cheetah enclosure in Kuno National Park appears to be a zoo, is it beyond the park’s buffer zone, and did park officials acquire the Central Zoo Authority’s approval?

Fourth, what legal guidelines apply to bringing exotic animals into a national park?

The WLPA contains explicit guidelines for granting permits for the removal of wild animals from national parks for zoos, but there is no information on file to address the issue of the introduction of exotic animals into either area.

Naturally, a state can now establish a government zoo on the edges of a national park’s buffer zone, where potentially exotic species could also be maintained with prior Central Zoo Authority clearance. But unlike Kuno, who intended to release African cheetahs into the wild, zoo animals cannot be released into the wild.

It is also important to consider whether a simple letter can take the role of a clause absent from a legal statute like the WLPA.

Before Prime Minister Modi released the African cheetahs, one hopes that the authorities carefully considered and addressed all of these concerns.

News Mania Desk