How Betrayal Ultimately Allowed An Impenetrable Fort City To Be Broken

Shah Abbas of Persia dispatched an embassy to India in 1603. In an effort to appease a regional monarch in the Deccan, it carried gifts and gems, including a crown covered in rubies. The local sultanates had long courted Persia, even submitting to its rule. Of course, they did this to further their own objectives. After all, the shah was a distant figure who was unlikely to exercise direct power. Nevertheless, the sultanates’ putative suzerainty gave them legal protection from Mughal claims to their lands. In other words, it was a balancing effort to court a rival power from a safe distance while holding away the empire closer to home. This lack of sincerity may have contributed to the Qutb Shah of Golconda’s refusal when the Persian embassy proposed marriage as a means of securing the alliance. The foreign ambassadors spent years at his court but were unable in completing this task. Golconda would give the Persian emperor ceremonial honors and kind words as a sign of respect. But it wouldn’t endow him with a princess daughter.

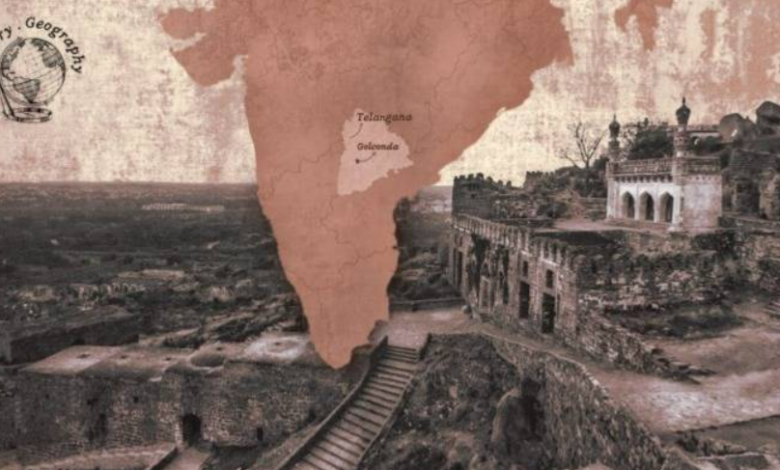

Golconda’s history is one of two cities and numerous powers. The Kakatiya dynasty originally constructed the massive fort, which still commands respect even now, before it was conquered by the Bahmanis. It was further developed in the 1500s by the first of the Qutb Shahs, another governor who rebelled against his overlords. Palaces and other structures were progressively constructed inside the intimidating stone rings that had taken the place of the mud walls. One of such impregnable fortifications, it was overthrown by the Mughals in 1687 due to internal treachery rather than a breakthrough in the defenses. Golconda is still a difficult proposition. One can practically see the victorious Mughal forces panting and heaving as they marched up to the imperial durbar given that visiting it requires trudging up boulder piles and through narrow corridors. The final Qutb Shah sat in this position with stoic dignity, wearing all of his trappings, and knowing that he was now a prisoner. In the hallways where he held court, there are pigeon nests and bat colonies. Glory left Golconda that day, and it changed from being a living, breathing place to an artifact.

On the other hand, a city next to the fort is where the legacy of the Qutb Shahs and their state is most present. The sultans of Golconda founded Hyderabad, an unwalled satellite town, in the 1590s. Some enthusiastic chroniclers compared Hyderabad to paradise, but in reality, it was built to expand after the fort became overcrowded. The Charminar, beside which the Qutb Shahs designed streets with bazaars, palaces, and other buildings, continues to be the city’s principal attraction. The no longer extant royal residence in Hyderabad is supposed to have been seven or eight stories tall; one floor included pillars and a ceiling covered in gemstones, with even the nails used to fasten the roof in place being made of gold. These symbols of Qutb Shahi splendor are thought to have been destroyed after the Mughal conquest in an effort to impose their own identity on the city. It’s also possible that the structures were destroyed during the last conflict. However, Hyderabad was unquestionably a jewel and a city all its own. Or, as an Englishman attested, it was the best place in India, with courtly halls that were more opulent than those built by the Mughals.

The Sultan-Quli Turkoman warrior who immigrated to the Deccan in the second part of the 1400s was the ancestor of the Qutb Shahi dynasty. As a Bahmani servant, he eventually came to become the Telugu region’s governor, the center of what he would later declare to be his own state. Sultan-Quli was assassinated at the age of 90 by an anxious son; the murderer, however, did not live long and was succeeded by Ibrahim, a sibling, who ruled for many years. Being a supporter of Telugu literature and having a Telugu bride, the Qutb Shahs in his era grew to be one with the land and their people. The main port of Golconda, Masulipatam, brought in wealth from textile exports, and its mines produced diamonds that were the stuff of mythology. While the court allowed for the presence of Persians, Southeast Asians, and Europeans, its government was run equally by Muslims and Hindus. In fact, two Brahmin brothers were in charge when Golconda was conquered by the Mughals, and it was via these brothers that Qutb Shah made friends with Shivaji, the Maratha hero.

It is hardly unexpected that the Mughals desired Golconda given its sizable revenue, reputable rulers, and reputed wealth. Of course, this region served as a gateway to the south, where Aurangzeb would later push the boundaries of his imperial authority. The state was made a vassal in 1636, and the Qutb Shahs were forced to swear allegiance to the Peacock Throne in order to stop considering the Persian emperor as a suzerain. The Mughals were once more at Golconda’s gates twenty years later, this time under the leadership of a youthful Aurangzeb. The queen’s mother, Hayat Baksh Begum, went and negotiated a contract, losing both territory and a princess. By deciding to remain in the Deccan, this begum—whom the Persian shah had previously courted—became one of the key players in Golconda’s politics. She didn’t achieve peace with her diplomacy; only more time. When Aurangzeb eventually made a comeback and his soldiers were unable to take the fort, bribery was used to help; one night, a mercenary unlocked the gates, allowing the enemy to enter. While the Qutb Shahs were being sucked up by doom, Hyderabad was being pillaged—even the doors’ hinges were removed.

The tombs of these long-dead sultans can be seen in the distance while looking down from the fort’s vantage point. These elegant buildings, which have been carefully restored by the Aga Khan Foundation, pale in comparison to the Adil Shahi monuments of the rival realm of Bijapur. These structures were severely damaged by rain and the brutal passage of time five years ago, and it has taken years to rehabilitate them. Ironically, during the last Mughal siege, these tombs were used as a military camps by the invaders. Aurangzeb even mounted weapons on some of them with Golconda in mind, shooting at the Qutb Shah from the graves of his own ancestors. Walking through the complex now, all these years later, one may find almost every main character from that era. The second Qutb Shah, who killed his father, is buried in a tower-like tomb; Hayat Baksh Begum is laid to rest adjacent to a magnificent mausoleum; a mosque is also named in her honor. And if you are familiar with their story and the legend of Golconda, it seems almost as though these people were alive yesterday and that their age has just recently come to an end.

News Mania Desk