Indigenous People’s are answers for combating the climate crisis !!

Naresh Sinha ,Guwahati

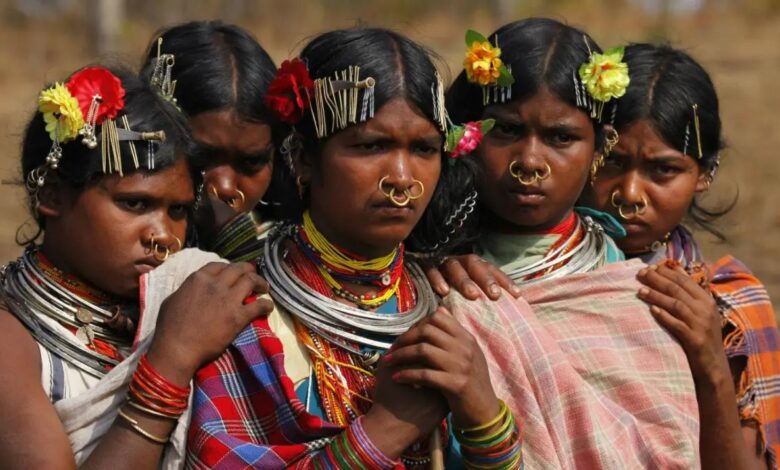

In light of the current climate crisis, hopes appear from an unlikely section of the world’s population, that is the indigenous people. People who were often called savages and lived in a place called undeveloped now seem to show the world how their way of life which is living close to nature is one of the answers for combating the climate crisis.

The guardians of lives on Earth

Even though millions of species are yet to be discovered, indigenous people who live in a territory that covers about 25 % of the world’s land surface with a population of 370 million only, are the custodian of about 80 % of the global biodiversity. With just a small population comprising less than 5% of the world’s population, and living in just a quarter of the world’s total land surface, the indigenous people had done commendable work in conserving the biodiversity in their regions. In India, the northeast region of the country is also known as a biodiversity hotspot.

The question that follows is why and how can this happen. How are the indigenous people able to protect the rich biodiversity in their respective regions? Thanks to the indigenous people and local communities who are the world’s biggest conservationists, more than 30 percent of the earth’s land and water are already conserved. The UN Environment Program, World Conservation Monitoring Centre/ICCA Consortium’s new estimates suggest that Indigenous peoples and local communities conserve at least a fifth of all land on earth. UN sources state that there are currently about 476 million indigenous people in the world in 90 countries. They live and occupy approximately a quarter of the world’s land and water. The area holds about 85 percent of the world’s biodiversity, and the indigenous people can therefore be called the keepers of the biodiversity.

The future is the indigenous way of life

“The future of our planet lies in indigenous ways of living on the Earth,” says Jon Waterhouse, Indigenous Peoples Scholar at the Oregon Health and Science University and a National Geographic Education Fellow Emeritus and Explorer. Waterhouse also says “As a global community, we have lost our way; we forgot what it means to have a relationship with the land.” It is however not easy to understand the complex relationship that the indigenous people have with nature. The indigenous relationship is much deeper than just conservation. The indigenous way of life is not only living in partnership with nature but it has to do with the holistic relationship that people have with nature.

Importance of the traditional knowledge system

Indigenous communities the world over lived in isolation. Often, it was because they live far from the crowd that they are able to protect their biodiversity. They protect their biodiversity because for them living in balance with nature is crucial for their survival. Hence a closer look at their way of life vis a vis the environment, it is found that they possess knowledge that connects them with the nature around them. Their traditional knowledge about changes in the weather pattern and other elements which influence the ecosystem they live in is appreciated by many.

In villages people still have traditional knowledge which helps them predict the weather and decide on the time they should sow their seeds or plant their crops. They are able to read the signs in nature by reading the changes in the plants or even in the way birds sing and insects make their sounds. These biological indicators have held them in good stead and recently during the lockdown due to the CoVID-19 pandemic, their knowledge of indigenous wild edibles helped them survive the pandemic.

The living nature

The first nations people shared another common value that animals, plants, and the spirits of nature are alive. Humans are not seen as separate from nature but as part of the earth; humans are as important as animals, and plants and they share a very close kinship relationship with their fellow beings. Hunting or fishing is done in calculated ways taking into consideration their breeding and eating habits. In Jaintia hills, people would not go fishing when the fish were breeding and in the past when people hunt, they perform rituals that go with it, and obeisance was paid when the animal was caught.

In the indigenous concept, humans are not seen as superior to nature, or rather nature does not exist to serve humans. Humans are supposed to live in peaceful coexistence with fellow beings. The idea that nature exists to serve humans is foreign to the indigenous people. They believe everything in nature coexists to support one another and not to serve the other. The word is coexisting not service as service is a capitalist idea that sees everything measurable in money terms or everything can be monetised. In a traditional context, the human relationship with nature is both profound and complex.

Indigenous people are their enemy

In the global scenario, indigenous people find themselves on the front line of the attack by industrial agriculture and logging. Their ancestral lands were seized for industrial purposes and in the process destroyed the biodiversity in these areas. Their mountains and rivers which they considered sacred were exploited often leaving hills barren and rivers polluted.

While in many cases, the environmental terrorism against the indigenous people was executed by outside forces, in some cases like in Meghalaya, it was carried out by the indigenous people themselves. No law or no amount of enforcement can succeed in preventing the destruction of the environment when the people themselves are hell-bent on destroying nature.

Our relationship with our values

we have chosen to detach ourselves from our relationship with nature; can we still call ourselves the indigenous people? When we only see natural resources as something to exploit, the question is what kind of relationship do we have with nature. Can we still call ourselves indigenous people when the relationship between ourselves and nature has broken?

The Sixth schedule which is supposed to protect us is used to exploit land and rivers for the benefit of the few. The Autonomous District Councils which are empowered to protect our culture, tradition, rivers and land are more often than not misused to serve the few. ADCs are now seen as just another government agency and not institutions that were empowered to protect the rights and the way of life of the indigenous people of the state. The need of the hour is to go back to our rich culture which includes living a morally upright life and living close to nature.

Indigenous values

Traditional values of the people comprise living a morally upright life, a caring and sharing community, and having a close relationship with nature. This value system is intricately woven into people’s way of life and it embodies the cardinal principles.

Indigenous values are central to the mission and programs of Woodbine Ecology Center. Although there is no single indigenous culture, there are common threads in the traditions of native peoples of the Americas that are worth remembering and integrating into our work. We believe that many indigenous values can assist us in addressing the fundamental social and ecological issues of our times and they directly inform our guiding principles. In particular, the indigenous values we look to are:

The Seventh Generation Principle. This principle states that we should make decisions about how we live today based on how our decisions will impact the future seven generations. We must be good caretakers of the earth, not simply for ourselves, but for those who will inherit the earth, and the results of our decisions. This value is found in the Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) Great Law of Peace (Gayanashagowa) and is common among a number of indigenous peoples in the Americas. We believe it is a sound principle, and it guides our policies and practices.

Respect, Humility, and Tolerance. Although respect, humility, and tolerance are not uniquely indigenous values, in the context of Woodbine’s mission, they are essential and extremely useful. In the fundamental laws or principles of most indigenous societies, from the Haudenosaunee to the Lakota to the Navajo, respect is integral to healthy and balanced relationships. In our relations with the environment, with our community, or in our personal lives, without self-respect and respect for others, we doom ourselves to imbalance, mistrust, and resentment. With respect, we appreciate the interconnection of all life and our indispensable part in the circle of life. With humility and tolerance, we appreciate that we are all in a constant quest for great understanding, wisdom, and contentment with ourselves and with life around us.

The lessons that allow us to more fully integrate these indigenous values into our lives, and into the programs at Woodbine, emerge from the total environment around us-and from the experiences and the insights that we bring to Woodbine’s vision.

The sacred teachings of respect, bravery, honesty, humility, truth, wisdom, and love are significant guidelines that resonate in most Indigenous cultures. The teachings are represented by seven sacred animals each having a special gift to help the people understand and to maintain a connection to the land and to each other. The values embodied in the teachings coupled with storytelling, and articulated through Indigenous language, reinforce Indigenous ways of being and doing. In other words, fortifying ethical thinking lends itself to ethical practice. They consider rivers and mountains their gods; hence have a very profound relationship with nature. The question is why have people not only lost their culture, but have sadly distanced them from their roots.

The indigenous people still have a way of how they manage their natural resources and it is now for the government to recognise the practice and make use of the wisdom.

Urgent need for an NRM policy

The state government needs to think outside the box and come up with a Natural Resources Management policy, which is based on the strength of the people’s way of life. When the world’s richest country, the G7 are looking at the lessons they can learn from the indigenous people to conserve at least 30 percent of their land and rivers by 2030, the state of Meghalaya with a huge population of indigenous people needs to go back to its roots and come up with lessons they can offer the world in combating climate change and that will be our gift to the world.