Recognizing Rosalind Franklin: The Nobel Assembly’s Opportunity for Redemption

The world is no stranger to prestigious awards, with the Academy Award celebrating excellence in film and the Nobel Prize honoring outstanding contributions to science and medicine. While the Academy often grants posthumous awards for special recognition, the Nobel Assembly has yet to follow suit. It’s high time that the Nobel Assembly rectifies this omission by awarding a posthumous Nobel Prize to British chemist and crystallographer Rosalind Franklin. Her groundbreaking research laid the foundation for our modern understanding of DNA.

The year 1962 witnessed the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine being awarded to biologists James Watson, Francis Crick, and Maurice Wilkins for their groundbreaking discovery of the molecular structure of DNA. At the time, scientists were grappling with the mystery of how a seemingly simple molecule like DNA could carry vast amounts of genetic information. Watson and Crick’s revelation of the double-helix structure provided the answer, revealing that DNA encodes information within the sequences of base pairs residing within the helix. This structure also explained how DNA replicates itself during cell division.

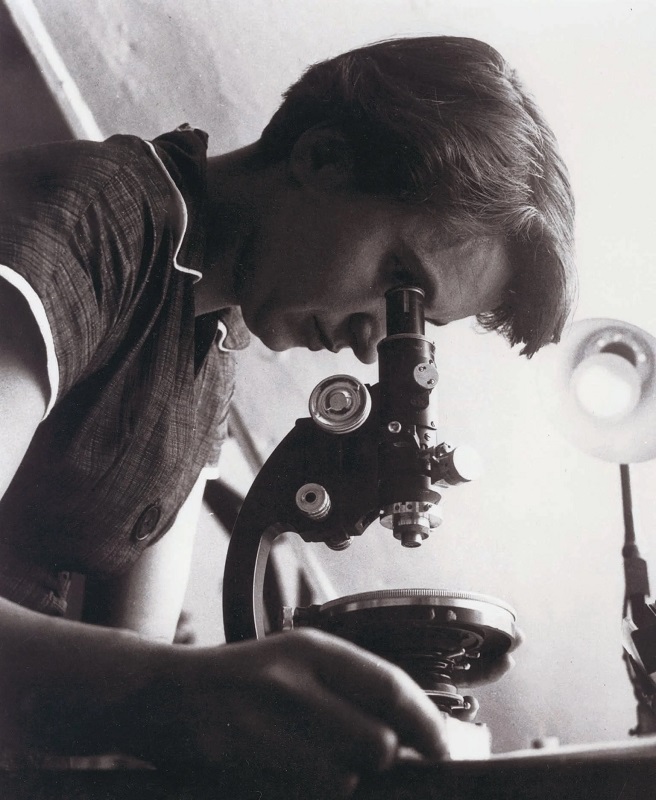

The 1962 Nobel Prize remains a subject of controversy not only because it recognized three men while omitting their female colleague but also because crucial information was acquired from Rosalind Franklin without her knowledge or consent. Franklin had produced essential x-ray diffraction images of DNA’s crystal structure, supplying crucial quantitative data in a report shared with a colleague who, in turn, shared it with Watson and Crick. Subsequent analysis of her laboratory notebooks revealed not only her deduction of the double-helix structure but also her recognition of how complementary strands could explain DNA’s capacity to carry extensive genetic information through “an infinite variety of nucleotide sequences.”

Despite publishing her research in a 1953 Nature paper alongside her graduate student Raymond Gosling, Franklin’s work lacked the impact of Watson and Crick’s groundbreaking declaration. Tragically, in 1958, Franklin passed away from ovarian cancer, likely a result of her exposure to x-rays in an era when laboratory safety measures were less stringent.

Nobel Prize rules stipulate that awards can only be granted to living scientists. Nevertheless, many believe that even if Rosalind Franklin had been alive, the Nobel Assembly would still have passed her over. This pattern of omission extends to other female scientists who made groundbreaking contributions to their fields. Prior to Franklin, only three women had received Nobel Prizes in science: Marie Curie, Irène Joliot-Curie, and Gerty Cori.

Furthermore, Franklin’s role in the discovery was significantly downplayed in the award citation. Maurice Wilkins, who was not an author on the pivotal 1953 DNA paper, also received a Nobel Prize.

Scholars and historians have worked tirelessly to correct the misrepresentation of Rosalind Franklin’s contributions. Recent commentary published in Nature by zoologist Matthew Cobb and historian of science Nathaniel Comfort reinforces that Franklin was an equal contributor to solving the DNA structure. Franklin did indeed grasp the structure’s implications, contrary to the implications made in James Watson’s best-selling 1968 book, “The Double Helix.”

The Nobel Assembly now has the chance to right a historical wrong by awarding a posthumous Nobel Prize to Rosalind Franklin, acknowledging her central role in unraveling the double-helix structure of DNA. Beyond Franklin, there are numerous instances of overlooked female scientists who also deserve recognition, such as Jocelyn Bell Burnell, Chien-Shiung Wu, and Lise Meitner.

News Mania Desk / Agnibeena Ghosh 25th September 2023