Unveiling the Truth Behind Bhansali’s “Heeramandi”: A Historian’s Perspective

News Mania desk/Agnibeena Ghosh/23rd May 2024

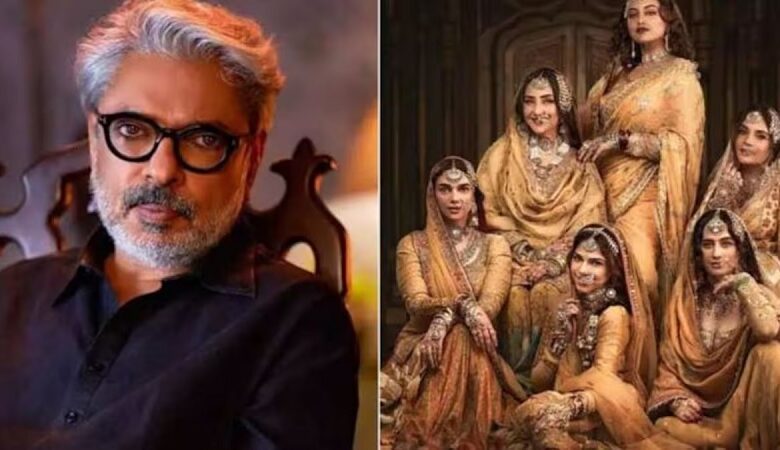

In the bustling world of cinema, where narratives are spun with a deft blend of fact and fiction, Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s latest offering, “Heeramandi,” has stirred both fascination and critique. Set against the backdrop of pre-Partition Lahore, the film conjures visions of a bygone era marked by opulence and intrigue. Yet, as one delves deeper into the historical annals, a different story emerges—one of stark realities obscured by the veil of romanticism.

A prominent voice in this discourse is that of a historian based in Lahore, whose reflections on “Heeramandi” shed light on the dichotomy between cinematic fantasy and historical truth. While the film mesmerizes with its depiction of a lavish mahal inhabited by courtesans, the historian notes that such grandeur is but a mirage. “As a historian, there are moments when I wish something in Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Heeramadi was actually true,” they muse. “And yet, except for the title, which is after an actual locality in Lahore, everything else is pure fiction.”

Delving into the origins of Heeramandi, or Hira Mandi, as it is commonly known, the historian unravels a narrative steeped in political intrigue rather than romantic allure. Contrary to popular belief, the area derives its name not from the brilliance of diamonds or the allure of its denizens, but from Hira Singh Dogra, a powerful courtier during the reign of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Far from being a haven of culture and refinement, Hira Mandi was initially established as a grain market, devoid of the romanticized imagery perpetuated by cinematic renditions.

Throughout the centuries, the history of Hira Mandi has been shrouded in myth and misconception. While some portray it as a bastion of high culture and sophistication since Mughal times, the reality, as the historian reveals, is far more nuanced. The decline of Lahore during Aurangzeb’s rule, coupled with subsequent invasions, precipitated the exodus of affluent patrons, leading to the area’s transformation into a hub of illicit activities.

The British annexation of the Punjab in 1849 further solidified Hira Mandi’s reputation as a center of vice, relegating notions of culture and art to the annals of history. Early accounts of Lahore paint a grim picture of the area, with references to prostitution outnumbering tales of artistic splendor. Despite cinematic portrayals romanticizing the courtesans’ existence, the historian underscores the harsh realities faced by the inhabitants of Hira Mandi, particularly in the lead-up to Independence.

Amidst the allure of Bhansali’s cinematic spectacle, the historian urges viewers to seek the truth beyond the silver screen. “While we enjoy the great cinematography of Bhansali, let us not confuse it with the lived reality,” they caution. Through meticulous research and historical analysis, they invite audiences to engage with the authentic narrative of their region—a narrative fast being distorted by cinematic fantasy.

In examining the historical tapestry of Hira Mandi, the historian offers a poignant reminder of the complexities that lie beneath the surface of cinematic depictions. As the allure of glamour fades, what emerges is a tale of resilience, struggle, and the enduring spirit of a community shaped by the tumultuous currents of history.