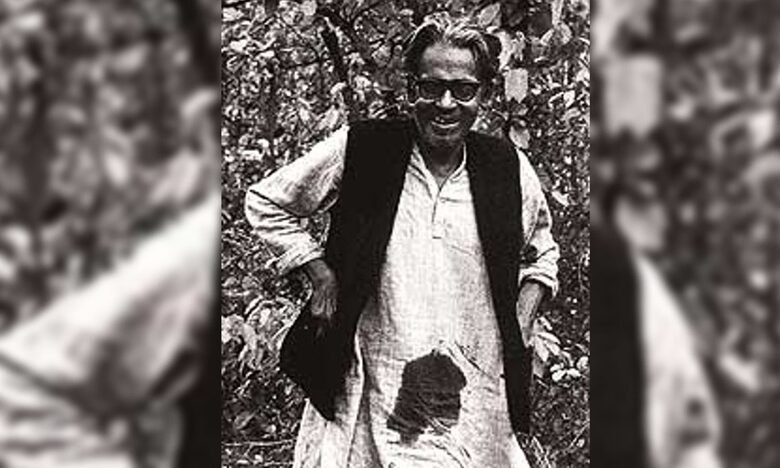

Ritwik Ghatak: The master who created art out of conflict, division, and pain

News Mania Desk / Piyal Chatterjee / 4th November 2025

Ritwik Ghatak, who passed away in 1976, was still alive in 2019, when protests both in favor of and against CAA were taking place around the nation. The sky above still appears darker as we commemorate the centennial of the birth of one of the holy trinity of Indian cinema, Ritwik Ghatak. Ghatak, the master historian of the Partition, skillfully and effortlessly depicted the world still obscured by displacement, identity crises, and political split. Ritwik Ghatak is still a star, though.

Ritwik Ghatak is 100 today, November 4. In 1925, Ghatak was born in Dhaka, India. Though unsettlingly so, Ritwik Ghatak’s themes are still relevant and connected to our times, whether it’s the fears of exclusion in West Bengal as the Election Commission performs the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls or the expulsion of migrants from the United States after decades of residency.

In addition to the themes of poverty, injustice, sorrow, suffering, and belonging, Ghatak’s plays and films grittily depicted resilience and energy, which continue to burn brightly in India and around the world. And Ritwik Ghatak will continue to exist as long as those challenges and solutions persist. Through the directors he influenced, the rebel filmmaker is still alive today. At home, Mani Kaul, Goutam Ghose, Anurag Kashyap, and Subhash Ghai; abroad, Martin Scorsese, Andrei Tarkovsky, and Jean-Luc Godard. The list is lengthy.

Ghatak is more than just a historical filmmaker; he is a dynamic force in art, politics, cinema, and political awareness. The Partition Trilogy (Meghe Dhaka Tara, 1960; Komal Gandhar, 1961; Subarnarekha, 1962) is one of his works that discusses the persistent human situations of loss, displacement, identity, and hope amid devastation.

Ghatak turned the Partition into a wound that sung, in contrast to many mainstream directors who handled it as a footnote in history. He did more than simply portray East Bengali refugees in Meghe Dhaka Tara, Subarnarekha; he also felt their division and conveyed it to the viewer. In his film, the anguish of being uprooted from one’s home becomes the narrative of the human soul’s quest for completeness. These topics are still pertinent in an era characterized by migration, exile, and broken boundaries.

For good reason, six of Ghatak’s classic feature films will be screened during the 31st Kolkata International Film Festival (KIFF), which will take place from November 6–13. Ghatak used a radical cinematic grammar. He employed music and montage as emotional shocks, shattered continuity, and blended myth and reality.

What appeared unpredictable or “too loud” at the time today shows how visionary he was. Ghatak’s experimental bravery is being carried by filmmakers all over the world, from Tarkovsky to Scorsese to the independent Indian filmmakers of today. Ghatak’s book Cinema and I was praised by Satyajit Ray, who claimed that it “covered all aspects of filmmaking.” Regretfully, Ray’s support did not result in Ghatak’s films receiving widespread acclaim during his lifetime. Ray became well-known throughout the world, whereas Ghatak was not even well-known in India.

Ghatak pursued truth on television, in contrast to his contemporaries who aimed for aesthetic beauty. The reality was unvarnished, awkward, and politically charged. Cinema, in his opinion, should awaken rather than calm. The life, era, and creations of Ritwik Ghatak serve as a mirror here as well, in 2025. Ghatak’s idealism felt like a moral compass throughout the 1950s and 60s, when art was frequently crushed by capitalism. He reminds us that art is more than just a product—it can be a cry.

“I have never made films for others. Truth be told, I don’t care if you dislike my films. I will do what I want to do, I will not go beyond that Till I am alive, I can never compromise… I will either live like that, or die trying,” said Ghatak in an interview.

There was more to Ghatak’s films—particularly the Partition trilogy—than just a country divided in two. Ghatak saw the Partition as a fracture of promise and betrayal, memory and modernity, rather than just a geographical and political division. Although freedom and independence have been attained, the fight to fully realize them is still ongoing. Ritwik Ghatak’s writings will speak to every generation that experiences identity loss, cultural disruption, or displacement.

The concerns of the contemporary world were predicted by Ghatak’s artwork. In the promise of the postmodern world, aren’t refugees without roots, art without money, and society without empathy still the norm? As long as these circumstances persist, Ghatak’s voice will reverberate. And as long as movies try to mend the damage caused by the past. Essentially, Ritwik Ghatak endures because he captured the pain and suffering rather than the moments. When wounds are transformed into art, they never go away. Through generations, they pulsate.