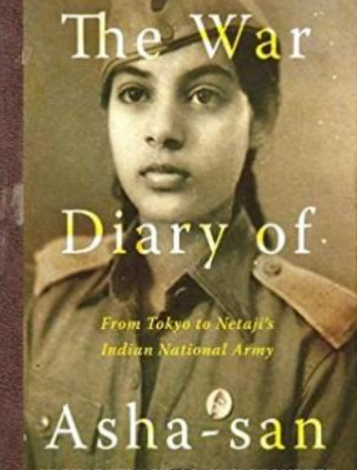

War Diary: This Book Details The Experiences Of Asha-San, Then 17, While Serving In Netaji’s Indian National Army.

Bharati Asha Sahay Choudhry kept a diary for more than 75 years, recording her daily activities. She was a young woman living in extraordinary circumstances, not your typical 17-year-old.

Anand Mohan and Sati Sen Sahay, her parents, were Indian National Army and Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose-affiliated liberation fighters.

Bharati, who was born in Kobe, Japan, in 1928, started writing about her experiences as a young child. She vividly recalled scenes of bombs falling, being trapped in trenches, having a father and uncle away at war, Netaji’s bubbly personality, and enlisting in the Rani Jhansi Regiment at the age of 17.

Asha-san received her primary and secondary education in Kobe before continuing her study at the esteemed Showa Koja College (now Showa Women’s University) in Tokyo.

Hers was an unpredictable life due to the war. The Second World War started.

After arriving in Tokyo from Germany in 1943, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose created the Azad Hind Government and the Indian National Army throughout East Asia.

Asha-san joined the Indian National Army, following in the footsteps of her father and her uncle Satya Sahay, and progressed to the rank of Lieutenant in the Rani Jhansi Regiment.

With the aid of her parents and a Hindi professor, Asha-san translated the Japanese version of the journal into Hindi after she returned to India in 1946, and it was serialized in the Hindi magazine Dharmayug. Additionally, it was turned into a book called Asha-san Ki Subhas Diary, but sadly, the translation contained several comical typos.

In order to reach a wider audience, Tanvi Srivastava, her granddaughter-in-law, has now translated her diaries into an English book, The War Diary of Asha-San (HarperCollins). The bravery of a young girl who was willing to risk her life for India’s freedom is highlighted in the book.

From Japanese to Hindi to English

Tanvi found the Hindi version of the diary on the bookshelf while she was stuck at home with her two small children during the epidemic and her safari firm was out of business. Till then, she hadn’t read it.

At about the same time, she submitted an application for the British Council’s Write Beyond Borders mentorship program for writers from South Asia and the UK.

She read a Jhumpa Lahiri piece over the course of the program that advised, “If you are wanting to write fiction, try translating. It’s a terrific method of learning the craft, getting inside a language, treating it like a literary apprenticeship.”

Tanvi was evidently familiar with Dadi’s life and her journals because she secluded herself in a room, and worked through the night translating the Hindi version after falling in love with it. It was a topic she would discuss in her mentoring meetings. They pushed her to finish it, and when she did, it was accepted by an Indian literary agent after being sent by her Bangladeshi instructor Saad Z Hossain.

“We have to take the necessary action”

With regard to the major choice in her life, Asha-san is quite a pragmatist.

The diary is filled with devotion to the cause and unwavering admiration for Netaji.

Over all else, it was about India. Furthermore, because he was always so pluralistic, it was never just about one religion. One state was never the focus.

Following her marriage to LP Choudhry, Asha-san had a rather solitary existence in Bokaro, and for the following 20 years, little was said about her experiences during the War. She converted her Japanese journal to Hindi in 1973 and published it in Dharmayug. She had a difficult life because shortly after her son’s death, her husband passed suddenly from cancer.

Asha-san was employed by a Japanese monastery in Bodh Gaya in the 1980s. She didn’t begin to receive recognition for her service in the Rani Jhansi regiment until the late 1990s and early 2000s.

But Asha-san is still of the opinion that she merely did what had to be done.

Despite the fact that Nehru and Netaji were close friends and that their ideologies differed, she claims that India wouldn’t have changed if Netaji had lived for another three decades because he wouldn’t have joined today’s politics.

News Mania Desk